Is Destruction the Inevitable Fate of Our Forests?

Fire in forest in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Photo by Rini Sulaiman / CIFOR

-Rini Sulaiman/Norwegian Embassy

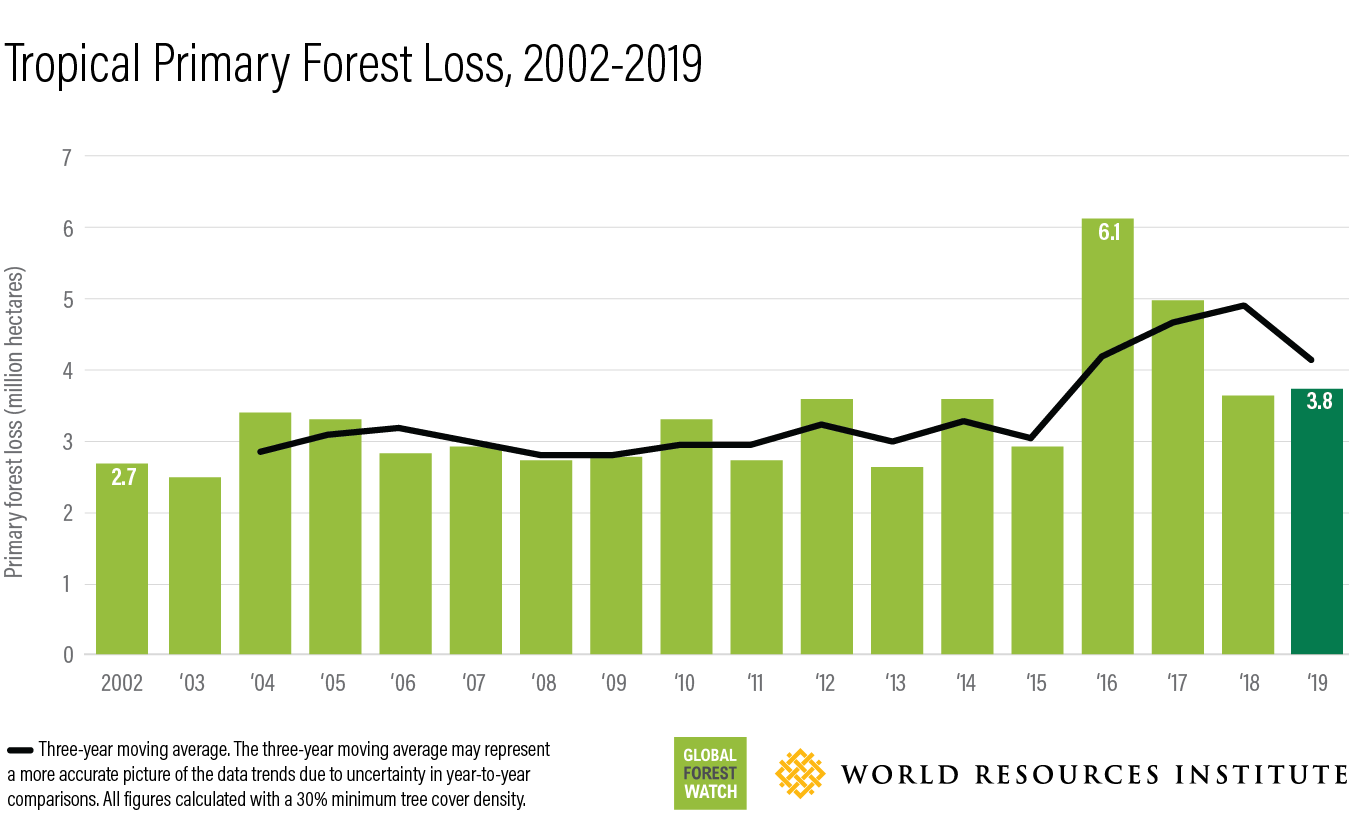

The world lost 3.8 million hectares (9.3 million acres) of tropical primary forests last year – an area nearly the size of Switzerland constituting some of the most valuable ecosystems on the planet for climate stability and biodiversity conservation. According to the latest data on Global Forest Watch, the area of forest loss in 2019, both overall and in such forest-rich countries as Brazil, the DRC, and Indonesia, was remarkably similar to the year before. Does this mean we’re stuck at this unacceptably high level of forest destruction, year after year, despite the many, varied efforts to stop it?

Not necessarily. Deforestation could get dramatically worse or dramatically better, depending on the road that we choose. Remember that all of the reported 2019 forest loss happened before any of us had ever heard of COVID-19 and does not reflect any impacts of the pandemic. It’s important to consider the 2019 numbers on their own terms, in the new light of current health and economic crises, and in the context of decisions shaping the recovery.

What do the 2019 numbers tell us?

As I wrote commenting on the 2017 numbers, we know how to stop deforestation. Thanks to ever-improving forest monitoring technology, we are getting better at attributing forest loss to proximate and ultimate causes, as well as identifying what interventions work to protect them. The 2019 data – both the good news and the bad news – provide several illustrations.

For example, we know that deforestation is lower in indigenous territories, and a mounting body of evidence suggests that legal recognition of indigenous land rights provides greater forest protection. It is disheartening to see hot spots of primary forest loss accelerating in indigenous territories in Brazil, following the administration’s signaling its intention to deliver on campaign promises to relax restrictions on commercial mining and agriculture in those areas.

We also know that well-targeted law enforcement works. Much of the forest conversion in the tropics is illegal, so enforcement of laws already on the books can go a long way toward halting deforestation. Indonesia marked a third year in a row of lower forest loss, due at least in part to enforcement of fire control measures and a moratorium on new clearing for oil palm plantations.

International financial and market incentives also have a role to play. Although it’s too soon to attribute causality, the downturn in primary forest loss in Ghana and Ivory Coast compared to 2018 could signal the effectiveness of corporate efforts to get deforestation out of commodity supply chains when linked to government programs, sometimes known as the jurisdictional approach to sustainable land use. It was in early 2019 that dozens of companies accounting for 85% of world’s use of cocoa announced how they were aligning their efforts with the national implementation plans of the two countries under the Cocoa & Forests Initiative.

The accumulating evidence of what does and doesn’t work to slow forest loss leaves no room for excuses for our collective failure to meet the goals of the New York Declaration on Forests, including the goal of halving deforestation by 2020.

What are the immediate implications of the pandemic?

At first glance, suffering and death caused by COVID-19 and the hardship of the accompanying economic crisis might seem unrelated to tropical deforestation. In fact, there are many direct links beyond the oft-cited origins of viruses in the wild animal trade. Here are three we should be paying attention to now:

First, prevention and control of forest fires – already an imperative as fire-related air pollution threatens public health – is now even more crucial as the coronavirus ravages the lungs of millions of people. While the 2019 tree cover loss numbers were lower than the fire-related spikes of 2016 and 2017, the still-significant fires in Brazil and Indonesia, and the devastation suffered by Australia and Bolivia in 2019 illustrate what we should not let happen in 2020.

Second, we should not let bad actors pillage tropical forests while law enforcement authorities are distracted and face limited mobility and constrained budgets due to the pandemic. Anecdotal reports of increased levels of illegal logging, mining, poaching and other forests crimes are streaming in from all over the world. Redoubled forest monitoring using near-real-time alerts can aid law enforcement authorities to respond quickly to illegal deforestation and raise public awareness of the problem.

Third, we need to distinguish between crackdowns on organized crime and appropriate actions to address exploitation of forests by people made desperate by the economic crisis. Faced with job loss, many poor people may turn to increased hunting and gathering of forest products or opening new subsistence agricultural plots. Temporary cash transfers and forest-friendly job creation are ways to reduce the need to rely on forests as a social safety net.

What role do forests play in building back better?

Consideration of forests in pandemic recovery efforts will determine if the tree cover loss numbers pivot up or down in the years to come.

First and foremost, now is not the time to relax environmental regulations in the name of attracting investment and creating jobs, as suggested by Brazil’s environment minister. By contrast, it is heartening that Indonesia’s Minister of Environment and Forests pushed back against and succeeded in reversing the Ministry of Trade’s suspension of that country’s forest legality program in the name of boosting timber exports amidst the COVID-19 economic downturn.

Instead of actions that postpone overdue transitions to more resilient, low-carbon economies to avert the looming crisis of climate change, governments now have an opportunity to accelerate them. Several elements of that opportunity have special relevance for forests.

Importantly, any corporate bailouts should be structured in ways that reduce, rather than continue, current pressures on forests. The aftermath of the Asian financial crisis three decades ago provides a cautionary tale of what not to do. In 2001, one of the world’s largest pulp and paper companies defaulted on $13 billion in debt, the largest corporate default in history at the time. The company’s business model had relied on fiber from Sumatra’s rainforests to feed its mills, and the terms of the restructuring agreement with investors allowed it to continue doing so after the crisis was over. Debt relief for private companies should instead be conditioned on shifts to deforestation-free supply chains.

Relief of sovereign debt could also be structured to encourage shifts to more sustainable land use. Debt-for-climate swaps have been proposed as a way to leverage transitions to low-carbon development, including so-called nature-based solutions to climate change. Building on the experience of debt-for-nature swaps that generate funding for placed-based conservation initiatives, the next generation of debt-related transactions could be expanded to include larger-scale investments to promote sustainability. For example, debt forgiveness could be tied to investment in green infrastructure (such as restoration of watersheds and wetlands), to changes in fiscal policies that reward companies and subnational jurisdictions for conserving forest cover, or to national-level performance on reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+).

However, another key lesson from the Asian financial crisis is the need for the international community to respect national sovereignty and work with domestic constituencies for change rather than impose unpopular reforms. The IMF’s 1998 Letter of Intent with Indonesia and associated World Bank structural adjustment loan included hastily prepared forest-related conditionality with little government ownership, and therefore little impact on the trajectory of land-use change. Positive incentives linked to progress on reducing deforestation, such as REDD+ finance and preferential investment and commodity sourcing, are more likely to be effective in eliciting needed change.

Which road will we take?

Regarding the 2017 tree loss numbers, I observed that forests often incur collateral damage in major economic and political events. This now includes COVID-19. We have a choice of two divergent roads. One set of policies could further accelerate deforestation, while another could catalyze the transformational shifts in land use necessary for climate resilience, biodiversity conservation and social justice. Our choice will make all the difference to the fate of the world’s remaining tropical forests, and the people who depend on them.

To cite just one compelling example, the science showing how rainforests recycle moisture in the atmosphere and generate reliable precipitation is getting stronger, with deforestation threatening agricultural productivity as much as hundreds of miles away. It would be ironic if we were to sacrifice tomorrow’s rainfall by raiding the world’s forests as a rainy-day fund today.