- Forest Insights

Drivers of Deforestation in Indonesia, Inside and Outside Concessions Areas

By Arief Wijaya, Reidinar Juliane, Rizky Firmansyah, Tjokorda Nirarta “Koni” Samadhi and Hidayah Hamzah

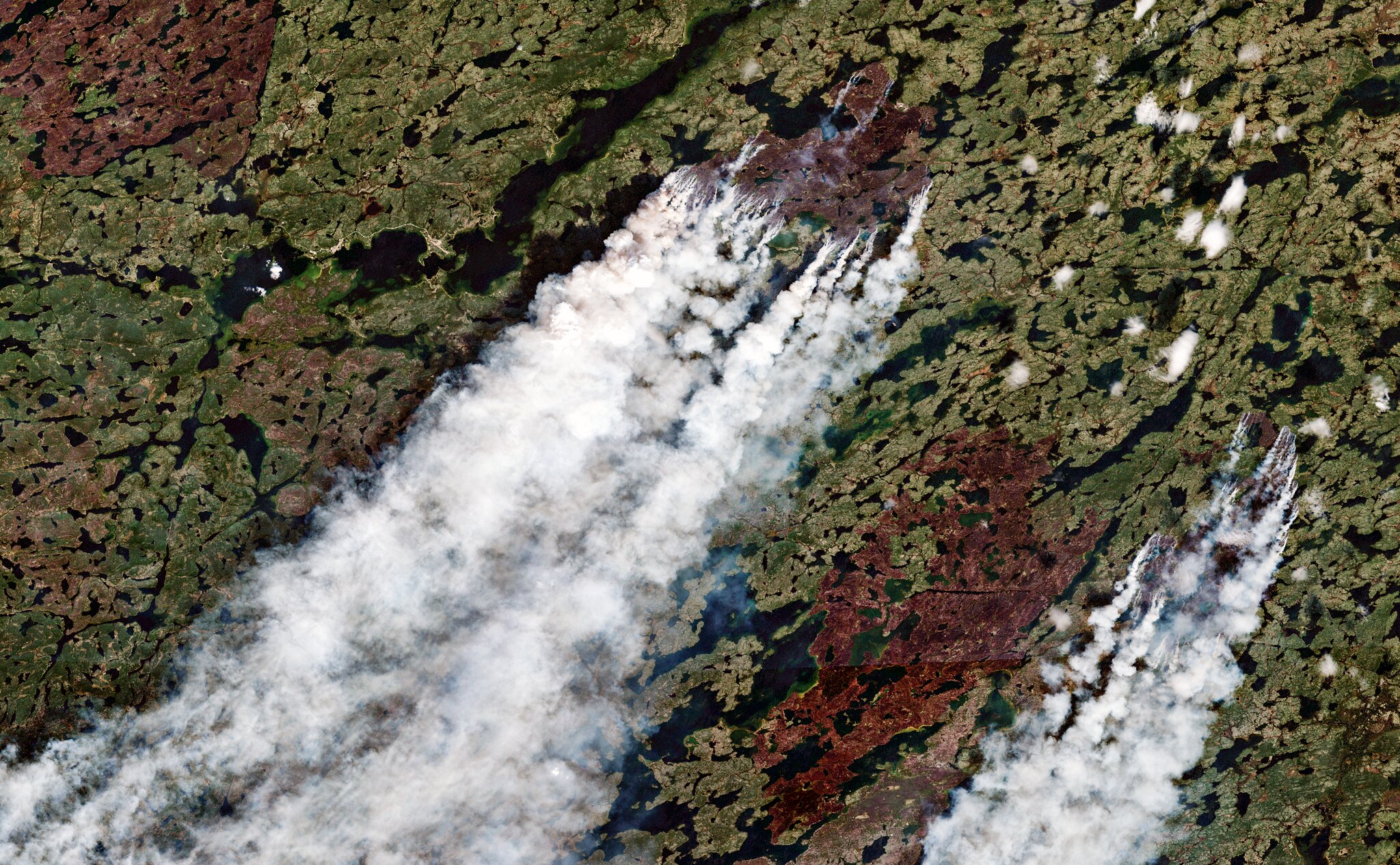

Oil palm plantation in Bogor, Indonesia. Photo by a_rabin.

Oil palm plantation in Bogor, Indonesia. Photo by a_rabin.Deforestation in Indonesia is an old tale. People know the rate keeps increasing, but they’re not quite sure why. Some blame the oil palm and pulp and paper plantations, but not everyone is convinced. While various studies suggested that oil palm plantations are obvious culprits of deforestation, others attempt to show otherwise. Recent media reports in Indonesia cited a study suggesting that oil palm does not drive deforestation since the plantations were not converted from forests – which is somewhat misleading. Critics fault pending legislation on palm oil as overly lenient on big companies and a potential threat to forest sustainability. To help clarify this heated debate, we analyzed data from Global Forest Watch to show that 55 percent of forest loss occurs inside legal concession areas, where removing trees is allowed to some extent, but 45 percent of forest loss took place outside legal concession areas.

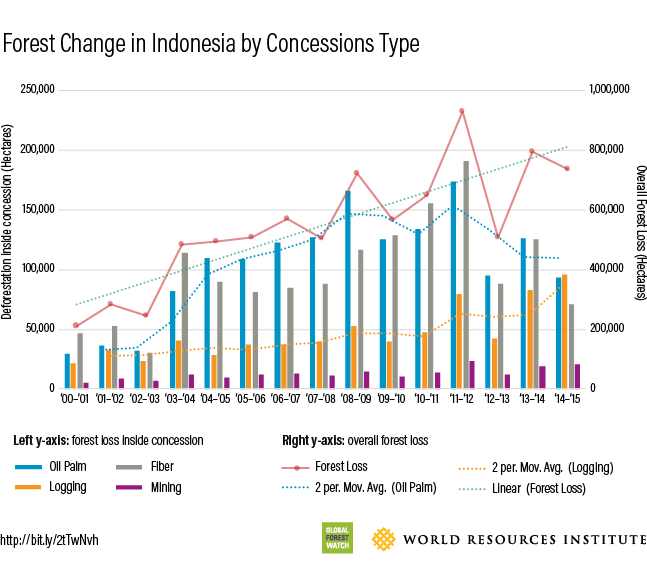

Figures on the left y-axis represent the forest loss inside concessions whereas figures on the right x-axis represent the overall forest loss.

Figures on the left y-axis represent the forest loss inside concessions whereas figures on the right x-axis represent the overall forest loss.Forest Loss Inside Concessions

Our analysis of tree cover loss within Indonesia’s primary forests and legal boundaries for oil palm, fiber, mining and selective logging concessions from 2000 to 2015 showed that approximately 55 percent of forest loss (more than 4.5 million hectares or more than 11 million acres) occurred inside concessions.

We also found that oil palm and wood fiber plantations, mainly for pulp and paper industries, were the two largest contributors to forest loss in Indonesia. Nearly 1.6 million hectares (4 million acres) and 1.5 million hectares (3.7 million acres) of primary forests—an area larger than Switzerland — were converted to oil palm and wood fiber plantations respectively. An interesting trend could be observed in 2012-2013 when forest loss inside oil palm plantations decreased significantly and stayed at the same rate until 2015. By contrast, forest loss inside logging concessions increased steadily from 2000-2015 and for the first time in 2015, loss inside selective logging concessions surpassed loss inside oil palm concessions, and this mostly occurred in Kalimantan and Papua. By regulations, forest clearing should not occur inside selective logging concessions where only trees with diameter at breast height (4.5 feet above the ground) of at least 50cm (19.7 inches) and has commercial value (such as Meranti) are allowed to be harvested.

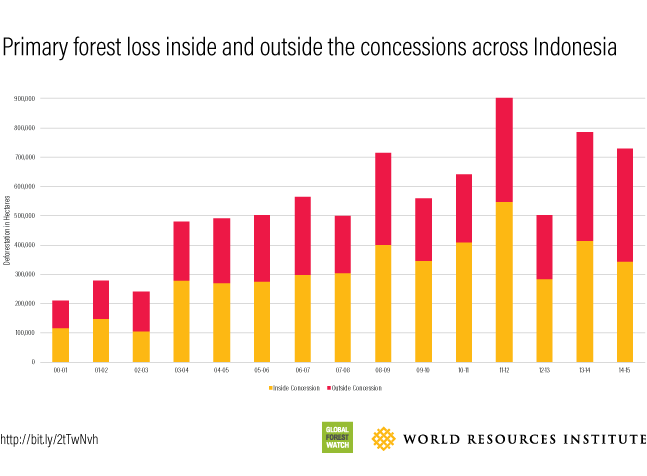

Forest Loss Outside Concessions

While one can argue that forest loss inside concessions areas is legal to some extent, forest loss outside concessions boundaries also took place at an alarming rate—3.6 million hectares or 8.9 million acres or roughly three times the size of New York City – since 2000. Much of this loss might come from those licensed concession holders who cultivate more area than the permit allows, or from excessive timber harvesting that leads to deforestation. The forest loss may also be driven by the vast network of small oil palm plantations operated by smallholder farmers who produce nearly 40 percent of Indonesia’s stock. Lack of data or official records about these farmers suggests that they operate outside of established concessions. Recent analysis also shows that forest loss outside the concessions was largely due to conversion of forested land to oil palm plantations.

What Next?

Our analysis suggests that in recent years, forest loss inside oil palm and fiber plantations concessions decreased, but mostly because expansion occurred outside concessions. Determining where deforestation took place outside the concessions area is beyond the scope of this blogpost, but several policies should be strengthened to prevent forest loss especially outside the legal concessions. Enforcing moratorium and expanding the scope of the moratorium to include secondary natural forests that are still high in carbon stocks and biodiversity would be critical not only to prevent forest loss outside concessions but also to prevent substantial carbon emissions from being released.

Given the significant forest loss outside the concessions that is presumably driven by unregistered palm oil operations, updated data is essential, particularly on smallholder plantation concessions whose data is limited. Making the data more comprehensive is the first critical step to understand where forest loss took place and to ensure better monitoring of forest loss outside concessions. Efforts to map smallholder palm oil plantations have been made by national and local government, private sectors and other organizations. However, those efforts are scattered, so the government should take the lead in synchronizing the efforts to achieve more meaningful impact.

With regard to concession data, we conducted analysis based on concession data issued in 2011 available on Global Forest Watch. To generate a more precise analysis in the future, we need an updated concessions data and hence data transparency is critical. Finally, given previous studies that suggest that companies often cultivate more area than they should have, strengthened law enforcement to prevent or drastically reduce illegal logging and trade as well as improved monitoring of companies’ annual implementation plan (RKT) are critical to tackle forest loss and reduce carbon emissions.