- Forest Insights

Indonesia Reduces Deforestation, Norway to Pay Up

Indonesia was one of the few tropical nations to reduce its deforestation rates in 2017, and it’s paying off.

Norway announced on February 16 that it will provide the first results-based payment to Indonesia as part of a REDD+ agreement the two nations established in 2010. REDD+, which stands for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, is a framework under the international Paris Agreement on climate change in which developed nations pay developing countries to protect their forests as a way of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Norway’s payment not only promises to boost forest-protection efforts in Indonesia, it can potentially inject more finance into REDD+ globally.

Indonesia cuts its forest losses

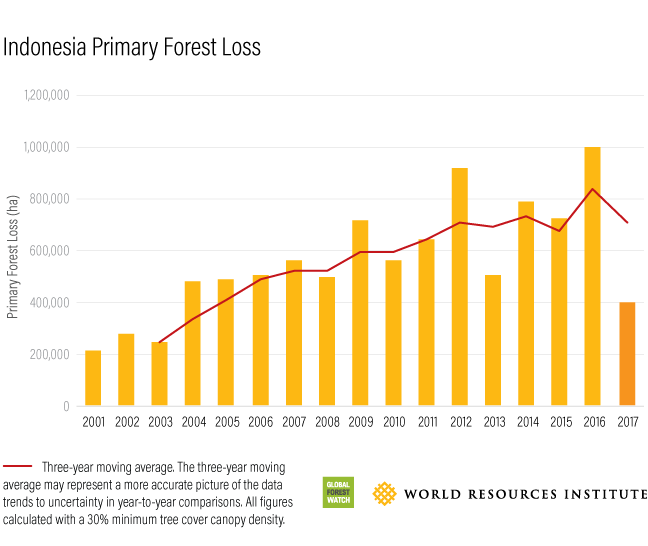

As reported by Global Forest Watch last year, Indonesia was a rare bright spot in the otherwise bleak landscape of 2017 tree cover loss. While most countries in the tropics contributed to another year of record-breaking losses, Indonesia experienced a 60 percent drop in primary forest loss compared to 2016:

This departure from the average over the last 10 years triggered Indonesia’s eligibility for results-based payment under the REDD+ Letter of Intent signed with Norway in 2010. Under the agreement, Norway’s payment will be calculated from estimates of forest emissions based on official Indonesian government deforestation data. (The comparison with Global Forest Watch forest loss data is explained here.) While the size of the payment is still under negotiation, it is likely to be at least $24 million in light of Norway’s commitment to pay for 4.8 million tons of averted CO2 emissions and a $5 per ton price agreed in previous REDD+ transactions with other countries.

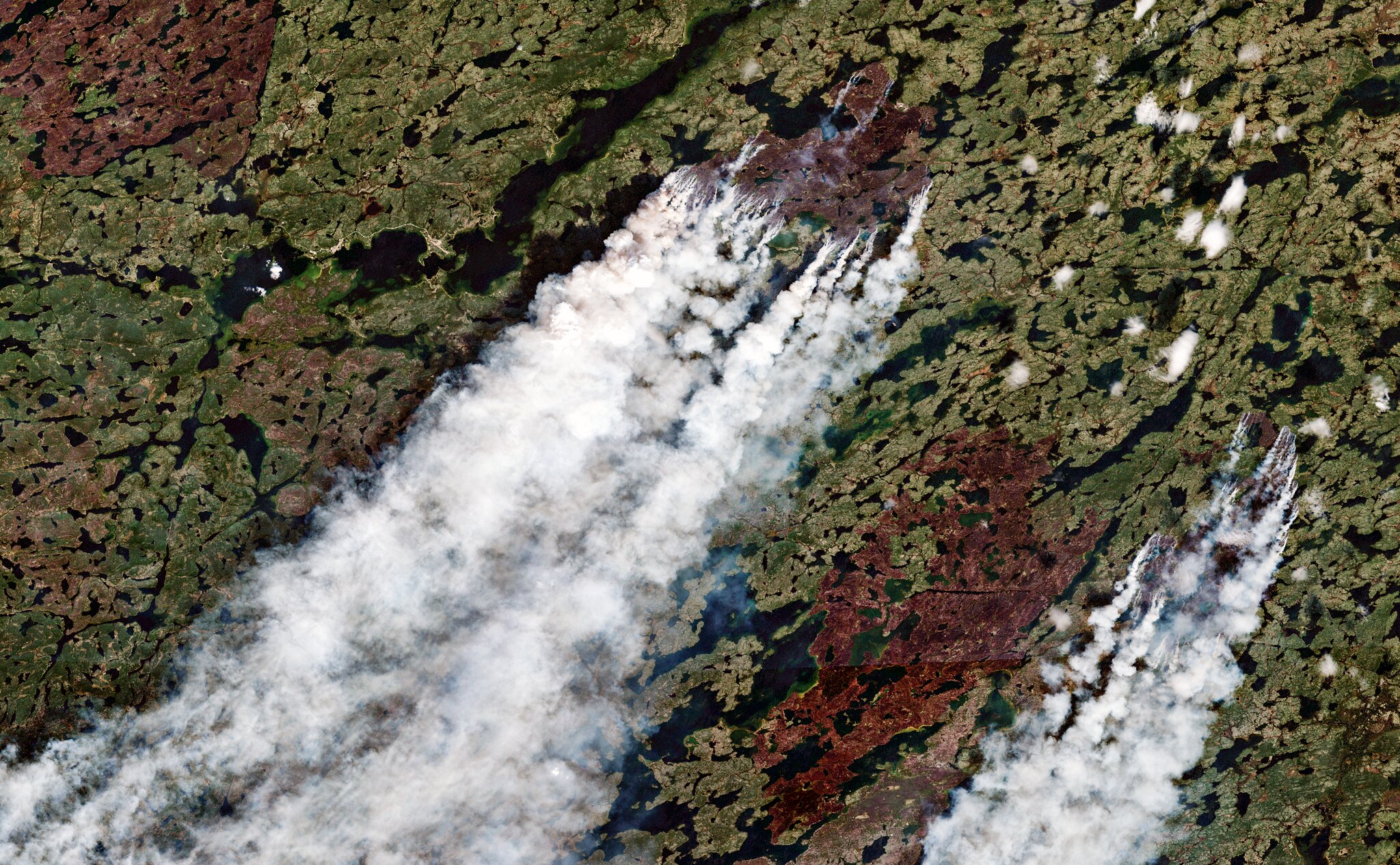

Multiple factors contributed to the sudden downturn in Indonesia’s forest loss and associated emissions in 2017. Favorable weather reduced the risk of repeating the catastrophic forest fires of 2015. Low prices for palm oil dampened incentives to expand oil palm plantations into forests.

Nevertheless, the Indonesian government can legitimately claim that its efforts contributed to the decline, having strengthened forest protection through new policies and enhanced enforcement. For example, a 2016 presidential regulation imposed a moratorium on the commercial development of carbon-rich peatlands even in areas already licensed for conversion to oil palm or timber plantations.

Whether or not the 2017 downturn will represent the beginning of a trend will be revealed later this year, when the 2018 deforestation and tree cover loss numbers become available from the Indonesian government and Global Forest Watch, respectively. Maintaining the lower rate of forest loss this year could pose a particular challenge, as scientists predict that 2019 will be an El Niño year, with high temperatures and dry conditions increasing the risk of wildfire. In addition, Indonesia will hold presidential elections in April 2019, raising uncertainty about the continuation of current policies. In a recent presidential debate, both candidates expressed support for ambitious palm oil-based biofuel mandates, which, if not managed properly, could increase pressure on forests.

For those reasons, it’s important to understand how Norway’s REDD+ payments could spur increased efforts to protect Indonesia’s forests.

5 reasons REDD+ payments are important for Indonesia

First, even though the initial payment from Norway will be small compared to the size of the Indonesian economy, it will shine a spotlight on the role of better forest management in meeting Indonesia’s climate-related commitments. Indonesia has pledged to reduce its emissions at least 29 percent by 2030 compared to business as usual, and up to 41 percent with international support (such as REDD+ finance). A signal of the international community’s willingness to pay for climate mitigation results through the REDD+ framework can only serve to raise the profile of opportunities to further reduce forest-based emissions.

Second, international recognition of Indonesia’s achievement provides an opportunity for a star turn on the global stage. Until recently, Brazil was regarded as the poster country for success in reducing deforestation. With Brazil’s deforestation rate ticking upward over the past few years and concern over the Bolsonaro administration’s policies, Indonesia could assert leadership in the fight to reduce forest-based emissions, especially at venues such as the UN Secretary General’s Climate Summit in New York in September. National pride could be an important source of motivation for continued improvements.

Third, qualifying for results-based payments could re-energize the REDD+ agenda in Indonesia. Although the launch of REDD+ negotiations in 2007 in Bali led to a burst of activity, stakeholder enthusiasm and engagement have waned as the years have gone by. That’s a shame because the REDD+ agenda incorporates multiple initiatives that are of keen interest to domestic constituencies in Indonesia. Earlier this month Dr. Ruandha Agung Sugardiman, director general for climate change at the Ministry of Environment and Forests, depicted REDD+ as the engine of a train, pulling behind it eight freight cars representing the country’s One Map initiative to harmonize government maps, protection and recognition of indigenous peoples, conflict resolution in conservation areas, fire prevention, law enforcement and more.

Fourth, follow-through on the bilateral agreement with Norway can accelerate implementation of sub-national REDD+ initiatives working their way through multilateral financing pipelines. Earlier this month, Indonesia presented to the World Bank-hosted FCPF Carbon Fund its plans for a jurisdictional-scale REDD+ initiative in the Borneo province of East Kalimantan; an agreement for results-based payments is expected to be negotiated later this year. A separate pilot in the Sumatran province of Jambi is also getting underway.

Fifth, progress on REDD+ provides a timely complement to international efforts to get deforestation out of commodity supply chains. Indonesia is currently involved in a bitter trade dispute with European countries that want to restrict imports of palm oil-based biofuels because they’re associated with deforestation. European support for Indonesia’s efforts to reduce deforestation signals the prospect of a counterbalancing reward for forest protection. REDD+ payments can also complement the hundreds of corporate commitments to No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) in commodity supply chains. Wilmar, a major palm oil trader and the first to make an NDPE commitment in 2013, recently reaffirmed and strengthened policies to achieve its goal of eliminating deforestation by 2020.

A payment 9 years in the making

Despite repeated delays, setbacks and criticism regarding its partnership with Indonesia, Norway’s parliamentarians and taxpayers stuck it out, and kept their offer of up to $1 billion in REDD+ finance open for nine years. As described in my book, Why Forests? Why Now?, co-authored with Jonah Busch, one of the reasons that donors withheld additional pledges of REDD+ finance globally was concern that already-pledged funding had not yet been disbursed. As Indonesia and other countries succeed in reducing emissions from deforestation and earning results-based finance, that excuse will evaporate.

Congratulations are in order for both Norway and Indonesia. Here’s hoping that further forest emission reductions are achieved across the topics, and that rich countries pony up more payments to reward them.