What are Primary Forests and Why Should We Protect Them?

Brunei Ministry of Primary Resou

Primary forests are some of the densest, wildest and most ecologically significant forests on Earth. They span the globe, from the snow-locked boreal region to the steamy tropics, though 75% of them can be found in just seven countries. But what sets these forests apart from your average backyard woodlands, making them so critical to protect?

Forests in their “final form”

Age is one factor in the formation of a primary forest, although there is no set birthday at which a forest becomes “primary”. All forests grow to maturity at different rates based on their environment, and some trees can even live thousands of years, so the term “old-growth” is highly relative.

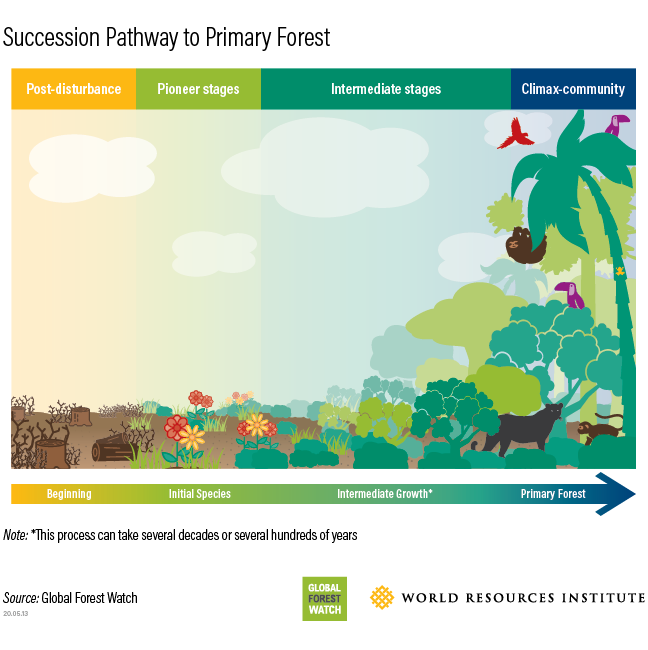

What matters more than age is a forest’s stage in a process called succession. In ecological terms, succession is the way in which ecosystems change from one state to the next following a disturbance. Take, for example, a fire searing through forests in Northwest North America. If it’s hot enough it will scorch everything in its path, leaving only charred wood and smoldering soil. When the smoke clears, nature gets to work rebuilding from the dirt up.

The first organisms to return are called “pioneer species”, typically fast-growing grasses, annual plants and other low, scrubby things that can take quick advantage of the now abundant sunlight. As these species live and die, they build up nutrients in the soil, allowing for a new guard of species to move in.

This replacement of species assemblages repeats itself as the years progress. Each new community inherits an environment better suited to its growth than that of the species that came before it. And so, over time the ecosystem begins to change. From the sun-loving grasses, to quick-growing softwood trees and finally to the tall hardwoods whose crowns knit together to form a thick canopy.

This final forest form is often referred to as a “climax community” and it’s these communities that are considered primary forests. The time it takes to return to full primary forest varies by the type of forest. In the Congo Basin, forest regeneration can take up to 50 years, for temperate oak and hickory forests, this process is documented to take around 150 years, but one study of Brazil’s Atlantic forest found it could even take millennia.

The most pristine places on Earth

Primary forests must also meet certain requirements of ecological integrity, showing little to no human interference. They can’t be disturbed for logging, mining, anthropogenic fires or road construction, or have their native species assemblage impacted by imported invasive species. They are dominated by continuous tree cover and must retain unpolluted soil and water.

Size and intactness are also factors in defining a primary forest. Cut a road from one side of the Amazon to the other and you’ve just divided one massive primary forest into two smaller ones. But do that over and over again, dividing the forest into smaller and smaller slices and eventually you end up with primary forest patches so small they no longer deserve the name. Although there is no official threshold of size for primary forests, the cutoff is usually considered in terms of whether the size of the forest allows for native species assemblages, natural forest structure and ecosystem functions to remain intact.

This pristine nature doesn’t mean that primary forests must be completely devoid of human presence, however. Many indigenous communities have lived within primary forests for hundreds of years, using forest resources sustainably to support their traditional livelihoods. Indigenous communities can be highly effective protectors of primary forests.

Why protect primary forests?

Primary forests comprise an estimated 26% of the world’s natural forest, with the remaining “secondary forests” falling somewhere in the intermediate stages of regeneration from recent human disturbance. So, if primary forests are barely a third of existing forest, why is it so critical we prioritize protecting them over any other?

Part of the answer lies in the shield they present against climate change. Primary forests are incredibly carbon rich; it is estimated that tropical primary forests alone store over 141 billion tonnes of carbon. The trees take in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as they grow, and store it in their trunks, leaves and soil. Once a forest reaches primary status it can continue to sequester carbon for centuries. Not only does clearing these forests release the stored carbon, it also reduces the capacity for them to sequester more carbon in the future.

The later successional stages also tend to have higher levels of biodiversity. The lack of human interference allows for ecological niches to flourish naturally, creating endemic species forming complex species interactions. Higher complexity within an ecosystem, is correlated to greater resilience and stability in the face of future disturbances. Preserving these forests also preserves cultural diversity, ensuring that traditional, indigenous ways of life are not disrupted.

By virtue of primary forests’ definition, human-driven tree cover loss within them is a concerning deforestation event. And because primary forests can take decades and even centuries to return to their undisturbed state, whatever we lose now, we may not see again in this century. Regeneration can be impacted by the type and magnitude of a disturbance. If there is no surrounding environment left to provide new seeds or seed dispersal is interrupted, forests may never grow back in the same way. Protecting primary forests now makes it easier for us to continue protecting them, and potentially restore them, into the future— paying it forward to a new generation.