Indigenous Communities in the Peruvian Amazon Protect their Forest Heritage with MapBuilder

Ranin Koshi at the 2023 Tech Camp organized by RFUS – workshop in Iquitos, Peru. Credit: RFUS.

“Just for monitoring, just for surveillance, our leaders have been killed,” recounts Ranin Koshi (in Shipibo meaning Strong Man, Hunter), the leader of Organización Regional de AIDESEP-Ucayali (ORAU) in Peru. The Indigenous communities ORAU represents have long recognized their territory in the Peruvian Amazon as the very essence of life. It’s the foundation of their culture, history and survival.

Yet, this deep bond with the land is under constant threat from illegal logging, deforestation, illicit crops, and other forms of intrusion. In 2001, Peru’s primary forest covered 69.1 million hectares, making up 54% of the country’s total land area. By 2023, the country experienced a 4% reduction of these forests.

Forest monitoring in communal territories has been going on for many years and has been embraced strongly, becoming a core part of the culture of Indigenous communities in the Peruvian Amazon. Despite the threats, these communities were able to decrease deforestation in their areas by more than 50% in just a year when using satellite data from Global Forest Watch (GFW) in their monitoring.

But more tools are needed to both protect forests and keep communities safe — in-person monitoring has led to dangerous confrontations and, tragically, the loss of leaders who dared to defend their sovereignty over their lands.

Now, Indigenous leaders in Peru are working collaboratively to develop new resources using MapBuilder, a tool that is helping them to control the data and narrative around deforestation in their territories and the threats they face to better work together, target solutions, and guard and defend their territories against latent threats to ancestral forests.

A history of forest monitoring using satellite data

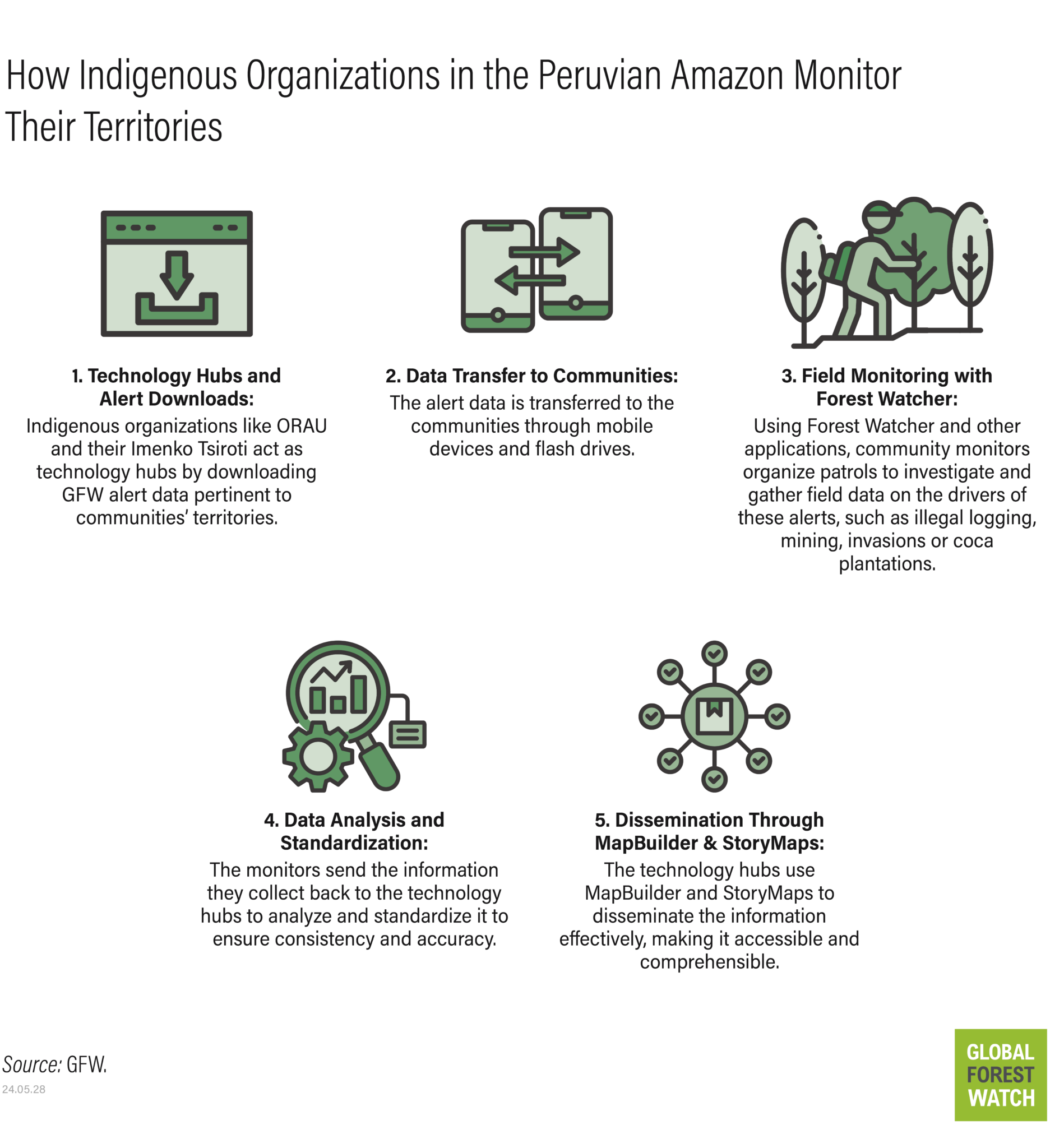

With support from Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS) since 2016, and organizations like ORAU, Indigenous communities in the Ucayali and Loreto regions have moved beyond traditional methods of territory monitoring, developing the technical capacity to collect and manage satellite data and analyses themselves. Gone are the days of relying solely on physical patrols and the unaided eye; now, satellite imagery and near real-time data paint a territory-wide picture of their land’s condition.

“Technology allows us to reaffirm and guarantee our rights, especially with regards to the territory, for our future generations,” says Ranin Koshi.

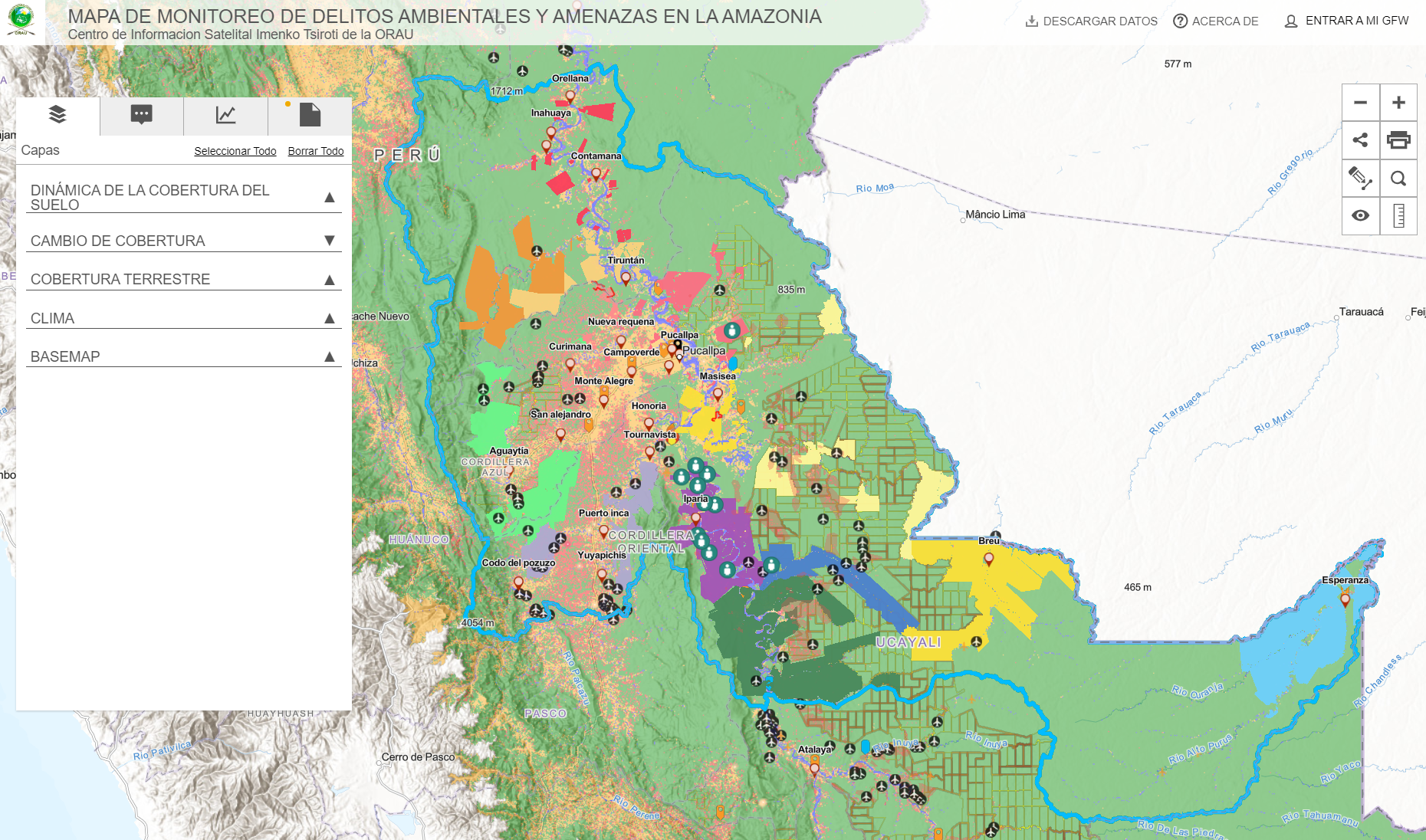

In 2022, ORAU created its Satellite Information Center, “Imenko Tsiroti,” to address deforestation and threats in communal areas with the support of RFUS and to meet the needs of Indigenous peoples for mapping and satellite information for monitoring, surveillance and land management. This center processes data collected by forest monitors, along with relevant GFW data on forest loss in their territories, to address the challenge of monitoring community forests in near real-time to prevent and reduce deforestation.

Since last year, ORAU has been promoting the creation of its Regional Indigenous Environmental Crime Monitoring Network, with the Imenko Tsiroti Center as its base and main hub. With the support of USAID’s PREVENIR project, it seeks to reduce the incidence of deforestation and crimes faced by Indigenous communities, as well as carry out strategic patrols and minimize the exposure of Indigenous vigilantes, monitors and/or leaders through the analysis of satellite data and technological tools.

A collaborative approach to visualizing data with MapBuilder

To help further advance Indigenous communities’ capacity, Peru’s Indigenous organizations identified MapBuilder as an ideal tool for Indigenous leaders to help visualize the data the communities are gathering from their territories about the threats they face and share it in dynamic format in their discussions and negotiations with external actors (such as government agencies, UN bodies and donors) without having to print and carry large maps. MapBuilder is a tool developed by WRI’s Data Lab that allows users to create interactive maps combining curated, timely, trusted global data — including data from GFW — with the user’s local data.

At two RFUS-organized Tech Camps in 2023 — a reciprocal educational experience designed to train participants in using satellite data and tools, and also to understand the communities’ needs and collaborate on what needs data and tools can address — the GFW team trained technical staff from the Indigenous organizations to customize MapBuilder to create their own online geospatial portals.

GFW also trained the organizations to create ESRI StoryMaps, which are useful to highlight specific issues such as video testimonials, photo galleries and narrative maps.

A main outcome of the Tech Camps was the creation of the ORAU geospatial portal using MapBuilder. This was possible due to the partnership between GFW, RFUS, the Indigenous organizations and the GIS mapping software company ESRI, participating as equal contributors in a process focused on shared learning and mutual benefit. Each contributor plays an important role in this process: GFW provides tailored monitoring data, the MapBuilder template, and training; RFUS convenes and facilitates the space for collaboration through the Tech Camps and offers crucial technical support on-site; and ORAU, through its Imenko Tsiroti Satellite Information Center, provides the data for the geospatial portal and functions as the data hub to collect field data generated by Indigenous communities as they patrol their territories informed by GFW deforestation alerts. This collaboration has been significantly advanced by the software licenses donations from ESRI, enhancing the project’s capacity for developing and maintaining tools like MapBuilder.

This collective endeavor, centered around joint exploration and development, leverages technology to directly integrate Indigenous partners’ knowledge and needs.

Telling the story of forest threats

Why, though, is visualizing information on a map so transformative? The answer lies in the map’s ability to contextualize data, creating a compelling narrative about the areas and communities it represents. A map tells a visual story, highlighting trends and priorities through the data it cross-references. For Indigenous communities, this means having the ability to prioritize resources and efforts based on timely, evidence-based data. For example, maps can leverage data from GFW on deforestation alerts and incorporate local insights on illegal activities, which in turn can help identify which community would benefit most from training monitors to detect illegal logging.

Through the use of MapBuilder, Indigenous leaders are creating online geospatial portals and StoryMaps, making the reality of their territories visible to the world. It offers an unfiltered, bottom-up perspective on the threats these communities face and their efforts to counteract them.

With tools like MapBuilder, the Indigenous communities and organizations that represent them control the narrative based on the data they are collecting and releasing to the public.

This shift towards digital storytelling and monitoring represents a significant milestone in forest protection. “There is deforestation; I can only say it. But now, I can demonstrate it physically with the ease of technology,” Ranin Koshi says, adding that this transition from manual to digital is revolutionary for the communities and their leadership. MapBuilder provides them with undeniable evidence of the challenges they face, transforming abstract threats into tangible realities that can be addressed and acted upon.

But that’s not all. With over 33 leaders assassinated in a decade, starting with Edwin Chota in 2014 and Quinto Inuma in 2023, by adding the location of the threats to Indigenous environmental defenders, the maps show the convergence of the threats with the deforestation drivers based on the evidence collected during the patrols.

Scaling collaboration to protect Indigenous-held forests

By integrating GFW data with communities’ field data into interactive applications, organizations like ORAU are fostering trust and enhancing collaborative efforts among community members and external stakeholders. The geospatial portals, developed using the MapBuilder template within ArcGIS Online, facilitate the seamless sharing of crucial environmental data, tailored to each organization’s specific needs and contexts.

Peru is just the starting point, signaling the potential for expansion within the Amazon Basin. Other Indigenous and local communities have begun to adopt monitoring technologies. For example, the Sarayaku People in Ecuador use monitoring technology to support the implementation of their territory management plan, and COCOMASUR protects the territory of 33 Afro-descendant communities in Colombia. At the regional level, the AIDESEP-COICA Early Warning and Rapid Response Alert System (SAT/RR-COICA) seeks to combine monitoring technology with a platform and protocols to respond to threats to Indigenous territories and peoples.

ORAU’s MapBuilder-based geoportal is more than just a mapping tool; it’s a testament to the power of collaboration between technology experts and Indigenous organizations and communities. The use of MapBuilder in Peru by Indigenous organizations can pave the way for its adoption elsewhere, and shows how technology, when shaped by the very people it aims to serve, can become a powerful tool in the preservation of resources.