- Users In Action

Smartphones and Satellite Imagery: The Indigenous Monitors of Vista Hermosa Take Action

This article is part of a series of blog posts produced with the Rainforest Foundation US. The series covers a training initiative for more than 36 indigenous communities in the Peruvian Amazon to use Global Forest Watch’s satellite and monitoring technologies for combating deforestation. Read the rest of the series here.

Smart phone in hand, indigenous Kichwa community monitor and regional leader, Betty Rubio Padilla, and a team of local forest monitors climbed into canoes and set off deep into the Peruvian Amazon. As they traveled, Padilla summoned the map on her phone. Recent GLAD deforestation alerts were showing a clearing in her community’s forest and she was determined to investigate.

Padilla lives in Vista Hermosa, an ethnic Kichwa community of roughly 40 families situated in the middle of the Napo River basin in Peru, halfway between the Ecuadorian border and the regional capital of Loreto, Iquitos. The Napo River, an Amazon headwater, is one of the world’s most biodiverse and carbon-rich areas. Relative to other river basins in the Amazon, its forests remain largely intact, having been spared, for now, from threats such as large-scale cattle ranching and forest clear-cutting.

Vista Hermosa holds a collective land title of 18,000 hectares of pristine rainforest, an area slightly larger than that of Washington, DC. As with most indigenous communities in the Napo region, the families of Vista Hermosa have sustained themselves for generations by living off the land and forest. The Kichwa sustain themselves through hunting, fishing, gathering fruit and firewood and medicinal plants. As a community that lives day to day from the land, this area represents their livelihood from generations before and for generations to come.

Threats on the horizon

In recent years however, their forest has been increasingly threatened by illegal logging and coca production, with illegal land invasions increasing in Loreto.

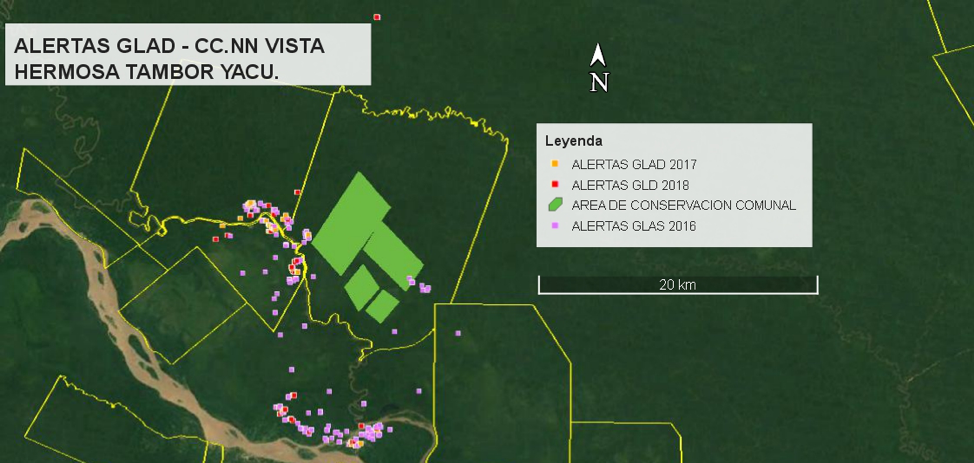

GLAD alerts visible near Vista Hermosa.

GLAD alerts visible near Vista Hermosa.In many cases, these land invasions are clandestine, occurring deep in the rainforest, invisible from river routes and roads, particularly if the objective is coca leaf cultivation for processing into narcotics. For coca growers, locally referred to as cocaleros, the outer limits of an area like Vista Hermosa are ideal — secluded and seemingly hidden from the eyes of the authorities. Often, if cocaleros discover that their initial clearing goes unnoticed, they quickly expand operations, burning dozens of hectares and establishing settlements. Moreover, cocaleros fish, hunt and extract valuable timber, placing pressure on rare or endangered species.

In addition to the environmental threats, these illegal operations are often linked to organized crime networks, which pose a threat to the indigenous residents the forest — such as Padilla and her family. However, equipping these residents with Global Forest Watch (GFW) data and smartphones is empowering people like Padilla to act.

Monitoring from above

With support from the Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS) and GFW, Vista Hermosa and 35 other indigenous communities in Loreto are putting GFW’s suite of forest monitoring tools and pre-programed smartphones to use patrolling their ancestral forests.

Vista Hermosa and the other communities have been regularly using satellite information provided by GFW since March of 2018 and so far, more than 4,000 deforestation alerts have been verified and over 2,000 patrols have been conducted. The communities elect their own forest monitors to be trained in the technology and lead patrols around their territory. Padilla serves as a monitor for Vista Hermosa.

With no connectivity deep in the Amazon, Padilla depends on hand-delivered printed maps and USBs that contain recent GLAD alerts. Alerts are transferred to the smartphone app Forest Watcher, which functions offline, essentially turning the phone into a custom GPS device.

Stopping deforestation in its tracks

Based on these maps, Padilla noticed an alert near a small offshoot of the Napo and set out to investigate. After months of observing GLAD alerts, Padilla was concerned that this patch of remote deforestation might be illegal activity. When she inspected the alert, her fears were confirmed. She found a clandestine camp that had just been abandoned. A trail led Padilla and her team to a series of cleared areas, recently burned and covered with newly planted coca plants, the raw material for cocaine, replacing the ancient tropical forest.

Padilla and her team of monitors consult the GLAD alerts on their smartphones.

Padilla and her team of monitors consult the GLAD alerts on their smartphones.Padilla and community monitors and leaders proceeded to destroy the nascent coca plants. Following the discovery, the community monitors presented the data to the community assembly. As is the protocol in collectively owned territories, where every community member is an equal landowner.

Vista Hermosa leaders agreed that the next step should be to summon the suspects, who were from the nearby municipality of Santa Clotilde. Shown the evidence, the perpetrators agreed to abandon the coca fields and allow the rainforest to retake them.

“The satellites allow us to make decisions in real time, and maybe deliver this information to State institutions for them to take immediate action,” said Jorge Perez, President of ORPIO, Peru’s regional organization of representing 15 distinct indigenous ethnic groups.

The community’s warnings, supported by satellite imagery, were enough to convince the invaders to cease their activity. This new capacity to take direct action has changed the way that the people of Vista Hermosa will govern their land, while sending a strong message to potential invaders: they are being watched from above, and the indigenous communities will find them from the ground.

For Padilla, the technology is crucial to better protecting the forest that has protected her community for generations.

“At the beginning, this technology was all new to us. Now, it has allowed us to know new areas,” Padilla said.

BANNER PHOTO: Boats on the River Napo. All photos by Tom Bewick/RFUS.