Satellite Data Helps Sri Lankan Forest Officers Patrol During Pandemic, at a Safe Distance

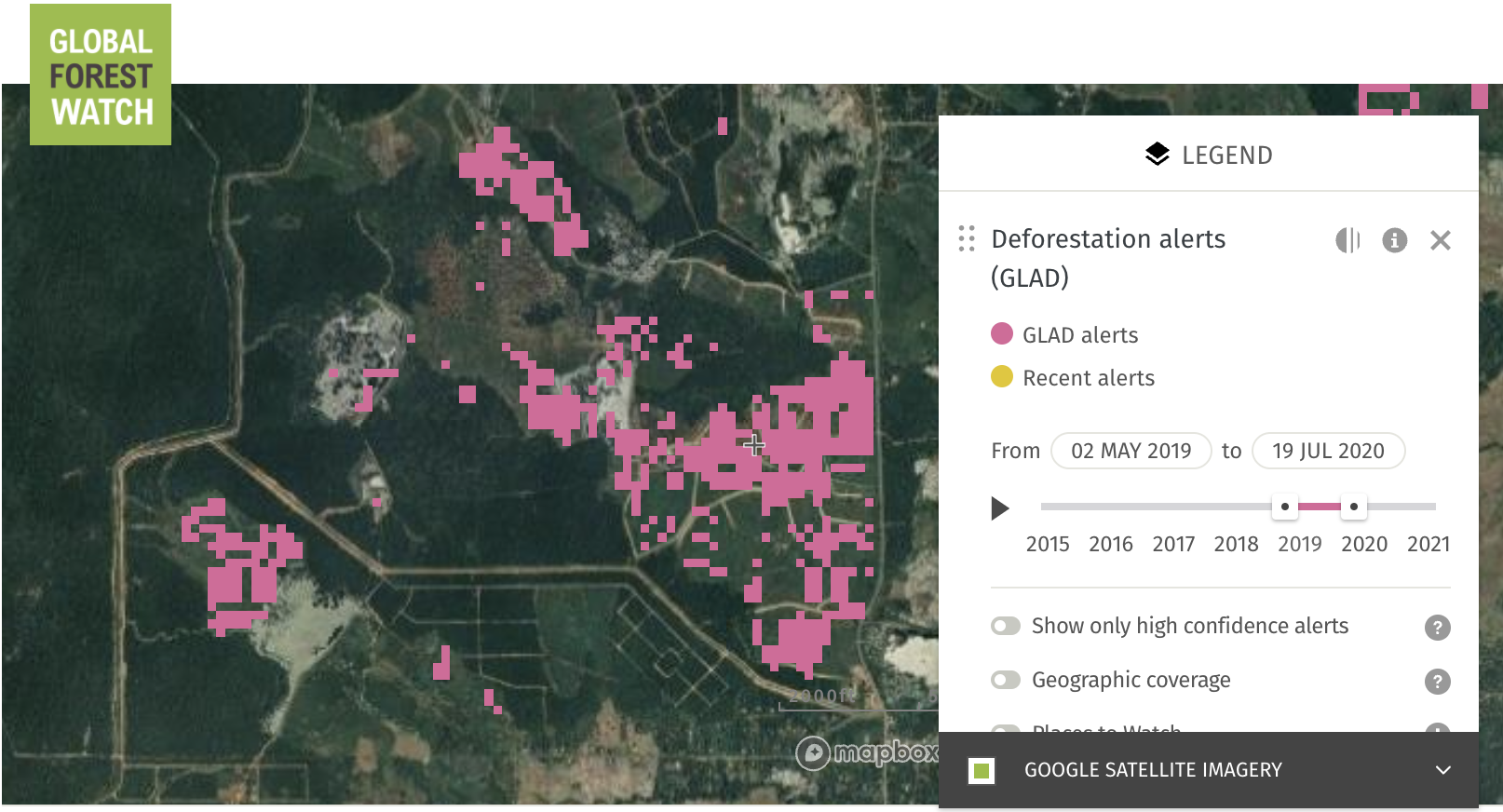

Encroachment in Kinniya, Sri Lanka detected with GLAD alerts. Photo by Tilak Premakantha.

On March 22, the entire country of Sri Lanka was placed under a strict two-month lockdown to combat the rapidly spreading coronavirus. Although the move helped curb the spread of COVID-19 (to date, there have only been 11 deaths in country), the restrictions provided an opportunity for illegal loggers to encroach on nature preserves. For the Department of Forest Conservation, safely protecting Sri Lanka’s forests in the middle of a pandemic meant getting creative with satellite data and the Forest Watcher mobile app.

Monitoring Sri Lanka’s diverse forests

The country hosts between 2 million and 3.5 million hectares of natural forest according to differing estimates. 596,000 hectares of these are ecologically significant primary rainforests. The Department of Forest Conservation monitors two-thirds of this natural forest, which has been declared as protected area under the Forest Ordinance of Sri Lanka. An additional 300,000 hectares of shrubland also fall under its jurisdiction.

Although Sri Lanka does not boast as much forest as larger nations like Indonesia, it is rich in biodiversity. Sri Lanka’s forests are home to over 30 endangered mammals, including the Sri Lankan elephant. Sri Lanka also has the highest species density for flowering plants, amphibians, reptiles and mammals in the Asian region.

According to Tilak Premakantha, a Conservator of Forests in the Geo-informatics & Forest Inventory of the department, these forests are mainly threatened by planned development. Chena, a native slash-and-burn, shifting cultivation practice that dates back centuries to early tribal societies, is another main driver of deforestation, along with forestry and commodity production.

Monitoring Sri Lanka’s forests for these threats is no easy feat even under normal conditions.

Prior to the pandemic, the department relied on a combination of routine patrolling, satellite imagery from Google Earth and reports from a network of community-based organizations and the general public. The forest officers responsible for investigating reports have other duties including running awareness programs on tree planting, forest plantation management and inventory and eco-tourism, so even at full capacity only about half of their time was ever dedicated to patrols. Conducting patrols is no easy task either, as forest officers could encounter anything from large elephant herds in dry zone forests to slippery hills that made for unpassable terrain in wet zone forests.

“We are not able to detect some of the encroachments on time, and these areas were subjected to permanent land use changes, thus reducing the forest area permanently,” Premakantha said.

COVID-19 spurs use of Forest Watcher among the department

These limitations were only exacerbated when the lockdown closed all government entities considered non-essential, including the Department of Forest Conservation. According to Premakantha, “[Forest officers] were permitted to travel only when forest offenses were recorded. Therefore, routine patrolling was restricted at the time. This created a good opportunity for encroachers.”

The department couldn’t sit idly by knowing encroachments were happening because officers were unable to patrol. However, they didn’t have the evidence to justify going into the field to investigate. Premakantha turned to Global Forest Watch (GFW) as a solution.

A few officers in the department had used GFW prior to the pandemic, but it wasn’t widespread.

“Restrictions in moving were an eye opener for us,” Premakantha said.

Since the beginning of lockdown, the department has produced manuals for staff on GFW and the Forest Watcher mobile app. Now, Premakantha refers to GFW whenever the department receives a complaint from the general public or the media about deforestation. He uses GLAD deforestation alerts and satellite imagery on GFW to check whether encroachment has been detected. If forest loss has occurred, then officers investigate in person, and the department can stop further deforestation and take legal action before the forest loss becomes permanent.

In one case, Sirasa TV, a popular local news channel, reported on recent encroachments in the Chundankadu Forest Reserve, claiming that the department had not taken any action to address it.

Responding to this assertion, the department used GFW to identify four areas of encroachment. The locations were sent to officers of the Trincomalee District, where the forest reserve is located.

After investigation, they realized one area had been officially released by the department for use as an irrigation project. Another site of encroachment had been previously addressed by the department through legal reprimand. The last two locations were detected in the field using GLAD alerts, and the department was able to take legal actions to stop these encroachments from expanding.

The department head, Conservator General of Forests, W.A.C. Weragoda, recognized the utility of GFW and decided to institutionalize its use in the department’s monitoring systems starting in July. They have set up a system for officers to verify GLAD alerts, record instances of deforestation and report these areas back to the head office, which will address any corresponding illegal activity.

Premakantha has great ambitions for how GFW will affect forest monitoring moving forward. “We hope that these tools will allow us to detect and take timely actions against all the illegal encroachment activities without missing a single one,” Premakantha said.